SCIBase: INHOSPITABLE 1.1 | Wellington Street, Leeds | November 2012

Home is where the art is?

As we leave behind the port of Liverpool and bring the work of SCIBase to Leeds for one final outing in 2012, ‘INHOSPITABLE 1.1’ becomes the marriage of three distinct exhibitions into one coherent narrative, driven by the input of all involved. Along with the shift in cities comes a shift in style and a new set of rules and curatorial concerns emerge. Gone are the white plasterboard walls of the Bridewell that emulate the gallery environment, gone also the separation between the individual concepts of the Bridewell and the Albert Dock. Here in Leeds we are presented with a Georgian mid-terrace, gutted and re-decorated to facilitate companies wanting city centre office space. Of course, at the moment, they are between tenants and this is where art finds a way in. The new plaster throughout renders the walls out of bounds and the fact that it is spread across three very large floors means a completely different approach to the display of work. For some this concept is easy, for others the boundaries are fixed so there is a need is to treat the individual with sensitivity and ensure an accurate and honest representation of that persons work or, if you will, voice. Over the course of the 2012 exhibitions, the method of presentation has varied wildly considering there are certain pieces that have remained throughout all three. In Leeds about seventy percent of the work has carried over from the Liverpool exhibitions with a couple of works being removed and some new pieces added, yet the feeling is of something completely new. No element of the building is left unused and some works are deployed in a more discreet manner in relation to their new, none gallery style, surroundings. The challenge in being given a building such as 64 Wellington Street is not to rely on the generally accepted methods of presenting art, but to take a broader view, one that acknowledges its surroundings and embraces its limitations. Any attempt to copy the gallery format here would be doomed to failure, so a curatorial sleight of hand is needed to almost con people into looking at art in a domestic context.

Down in the semi darkness of the Basement, also the entrance to the exhibition, the collaborative theme remains as with the Albert Dock show only here it is augmented by the work of Debra Eck, a text piece designed as a leaflet to be taken away. The sickly glow of television screens, ‘Circuit’ by Sean Kaye and Jenny West, and the light box designs, part of ‘Noumenon’, by Alan Dunn & Martyn Rainford, are the main source of illumination lending a subterranean feeling to the exhibition as you first walk in. ‘Noumenon’ by Dunn and Rainford also includes a sequence of graphic designs and a 12” vinyl record designed to be operated by the public. The record player sits on the floor surrounded by the sleeves of the record and a stack of free CD’s also designed to be given away. Every now and then, when the record is played, the sounds of electronic music and a child reciting phrases in a broad Merseyside accent float up through the building, quietly invading all areas of the exhibition. Alan Dunn represents a very literal connection between Leeds and Liverpool; whilst everyone else has a link with one of the two main cities involved Dunn has a foot in each camp, as resident of one and lecturer in another. Halfway through the exhibition’s two week run an extra artwork is inserted secretively by artist Jean McEwan. The piece is a zine which has been slipped in amongst the free leaflets on the desk and is, I presume, also intended to be taken away. In the same way as the exhibition, in all of its re-iterations, has played with the conventions of presentation depending upon the nature of the venue, the artists involved in the SCIBase project have also had a tendency to play with the expectations of the audience.

Moving into the rest of the house, three pieces by Swedish collective ArtMobile are placed in almost exactly the same conjunction as they were at the Bridewell in Liverpool, only here the effect is completely different; less to do with art objects, more a subtle intervention, as they take over the cupboards in the kitchen. WalkerHill take up the liminal spaces of the building adorning windows or lurking in toilets and corners, whilst a series of screen prints by Sarah Dale and photography by Andrew Crighton are hung in the hallways linking the rooms together.

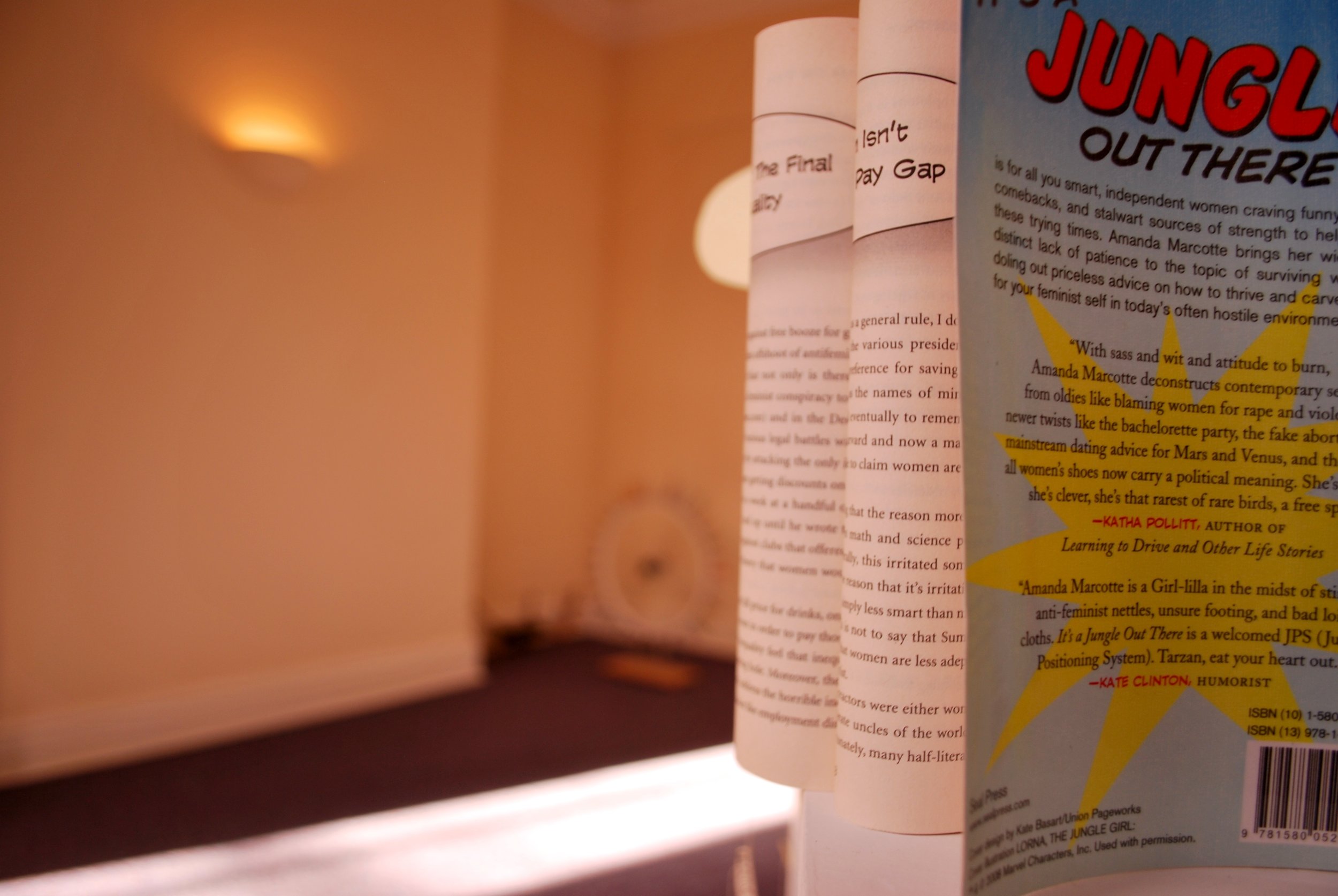

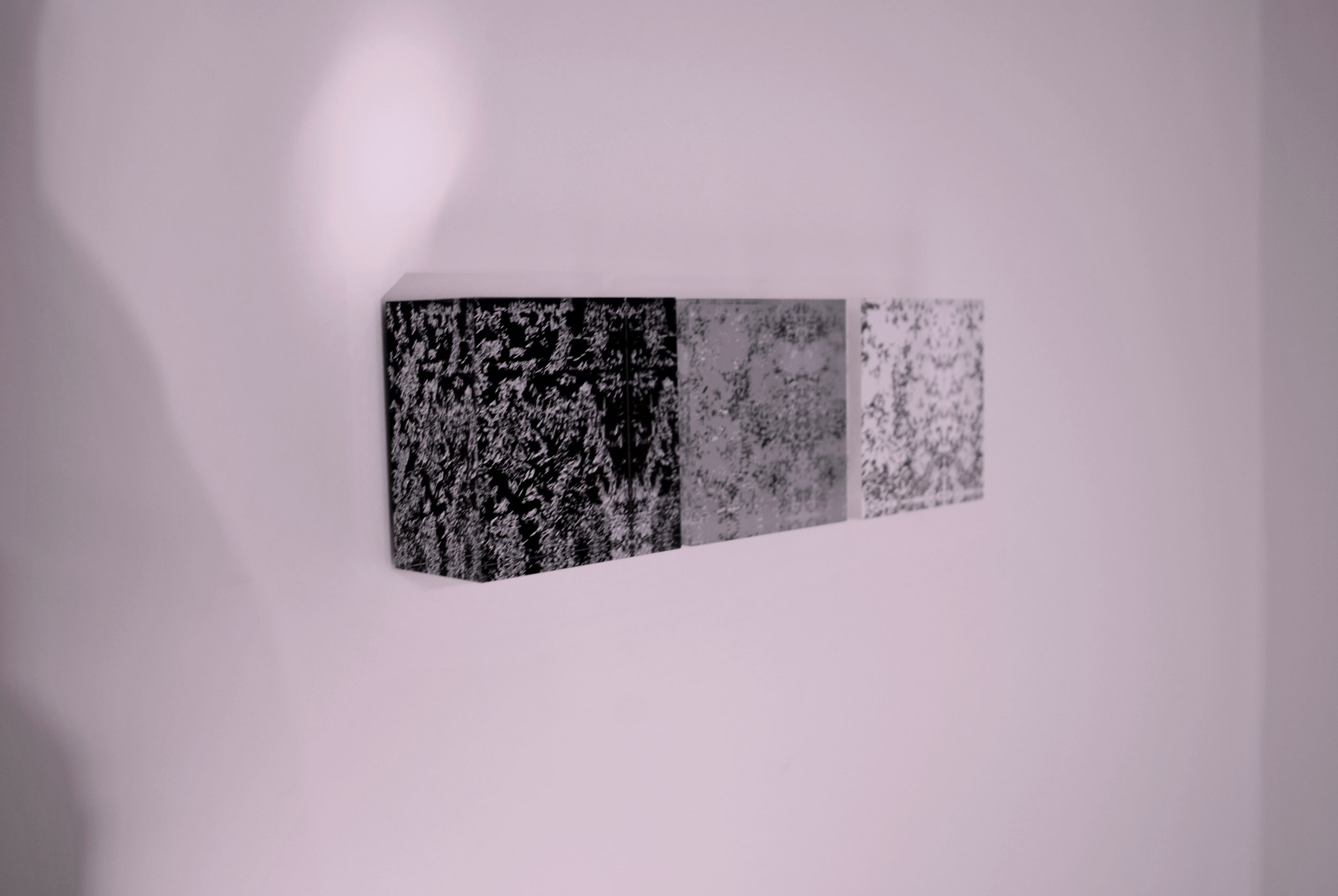

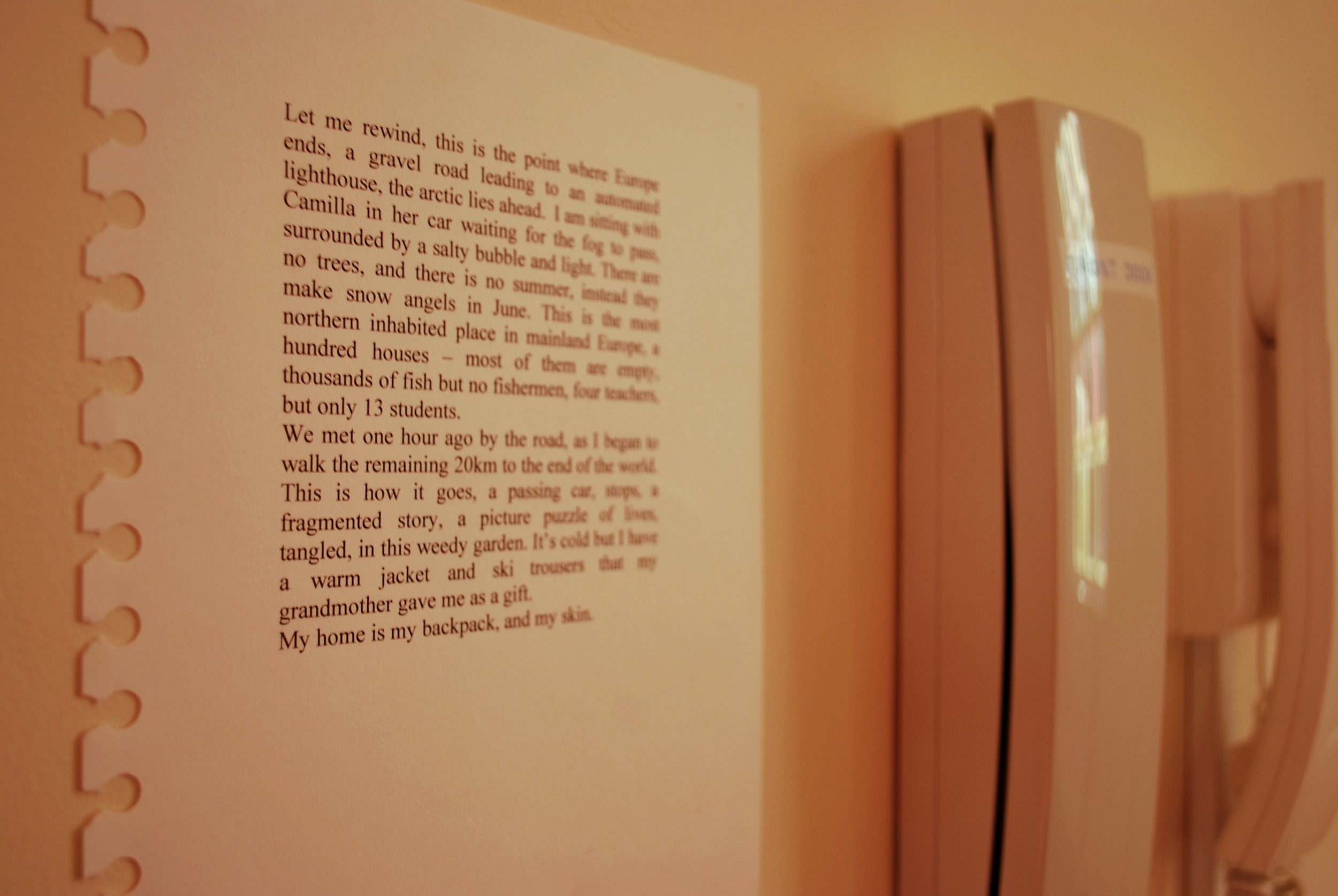

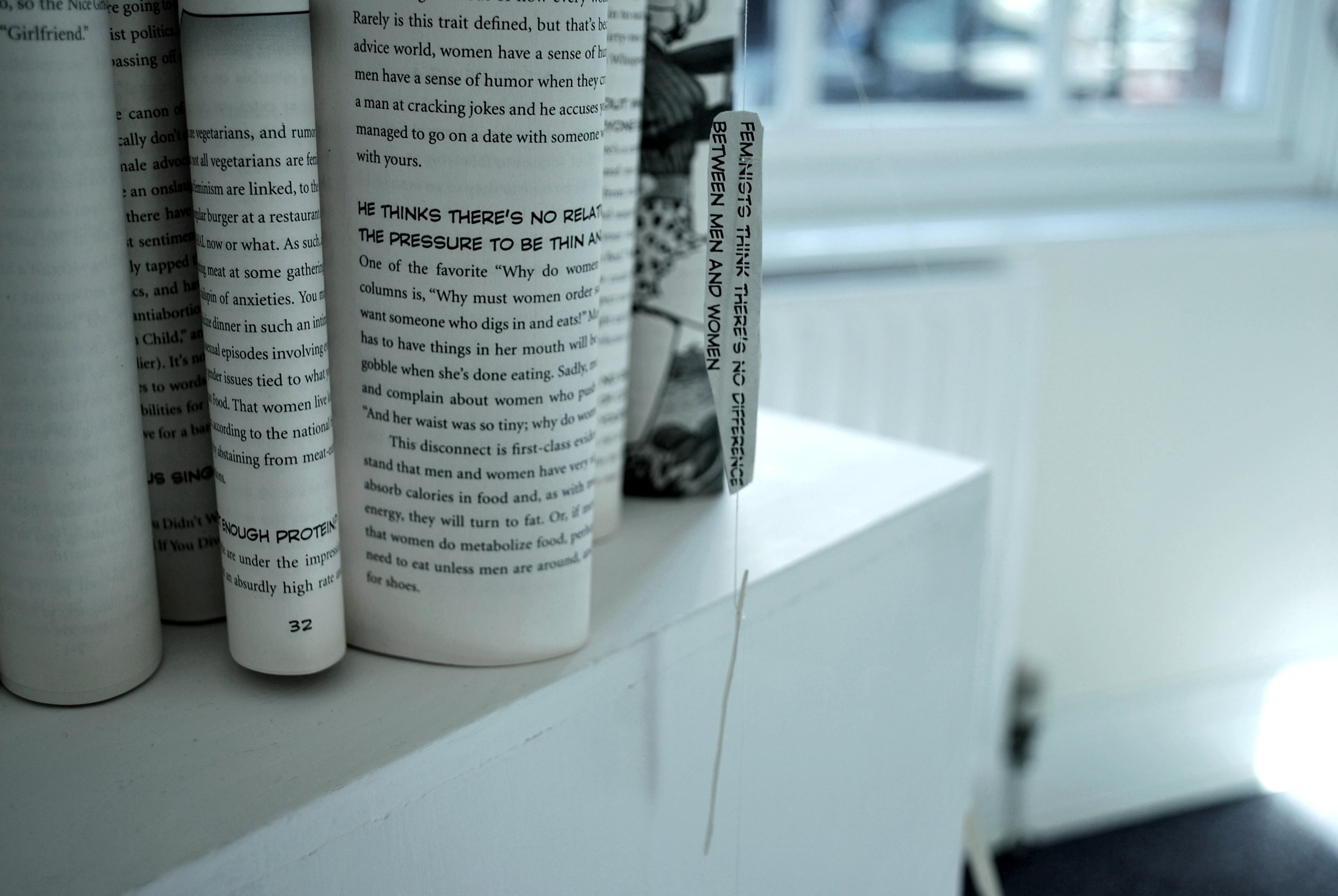

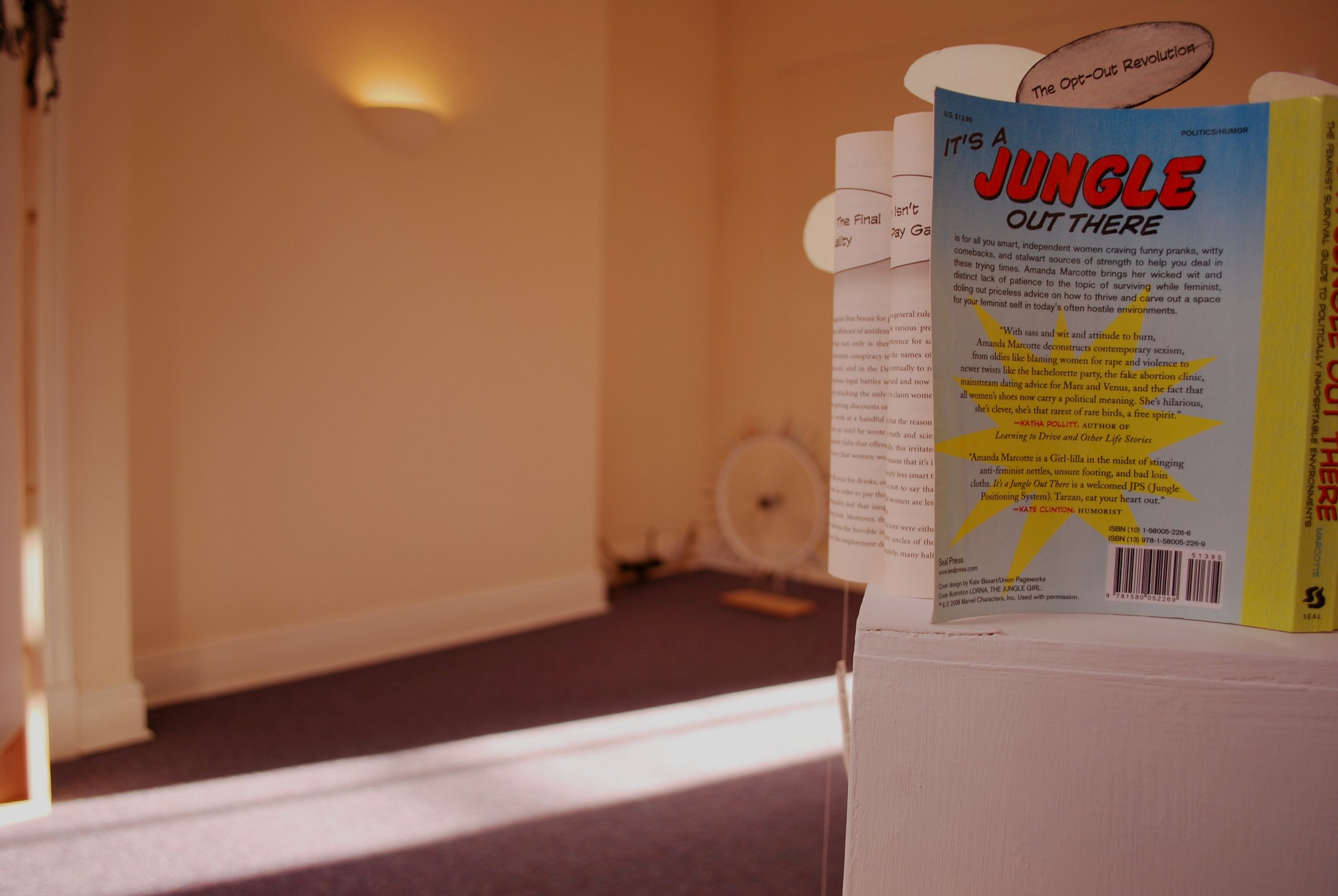

Residing in the first ground floor room that you reach is the work of Carol Ramsey, Julie Dodd, Jean McEwan, David Cotton and Wendy Williams. At 64 Wellington Street Dodd’s work is a much denser installation than at the Bridewell. An open frame has been constructed in the corner from which Dodd’s suspended paper tree’s reach out. In conjunction with Williams’ ‘Unicycle’ (2012) that utilises dismembered bicycle parts and a pair of antlers, an unusual gift to Williams from a Norwegian gallery, they create a feeling of solitude and abandoned nature, lost in a harsh wilderness amongst misplaced wildlife; a feeling compounded by David Cotton’s delicate, barely there pencil drawings on brown paper of some unspecified ocean dwelling creatures. The sparse surroundings and space between each work give a deceptively expansive feeling to what is actually a fairly small room. Jean McEwan and Carol Ramsey both utilise words in their work, also in this room, with Carol Ramsey’s book espousing feminist ideology, dismembered and reconstituted as something else, very much in the manner of Williams’ ‘Unicycle. McEwan’s work, a typewritten piece of carbon paper, in this setting is placed not on a wall but in a window overlooking the rear of the building. During the day the sun shines pin pricks of light into the room through the holes made in the typed surface whilst up close words are just about visible on this undulating blue / black cartographic landscape. In the adjoining room Alfie Strong’s ‘The Well’ (2012) sits at the centre of the floor, challenging the viewer to define its true meaning, a partial detail of a work in progress or a complete story that resists resolution? There are no true answers only more questions. Kelly Cumberland’s Stockholm work ’Vestigium Pulvis’ (2012) is reprised here with an extra section in grey now added between the original black and white portions. Cumberland’s projection from the Albert Dock exhibition in Liverpool is now clicking away in the window, a flickering image that can be seen by passers-by on Wellington Street, the curious wispy strands of these slides blowing gently in the internal breeze created by the projector fan. Higher up in the same window the work of Walker Hill creates a colourful border around the view of the outside world. The Inhospitable nature of contemporary culture is hinted at by a small sequence of collages and defaced hand-outs on the facing wall. The contents of the centre pages of the Sun are elevated by the presence of a frame whilst beneath it a naked and debased princess sits amid a jumble of the fortnights most sordid tabloid headlines. A defaced gallery hand-out occupies a frame next to an essay on ‘Graphic Interventions on the Photographic Surface’ as if trying to start a silent debate. Where does childhood end and adulthood begin? ‘Are we confronted with yet another instance where mass consumption capitalist economy expands into a taboo area in order to transform private behaviour into a commodity?’[1]

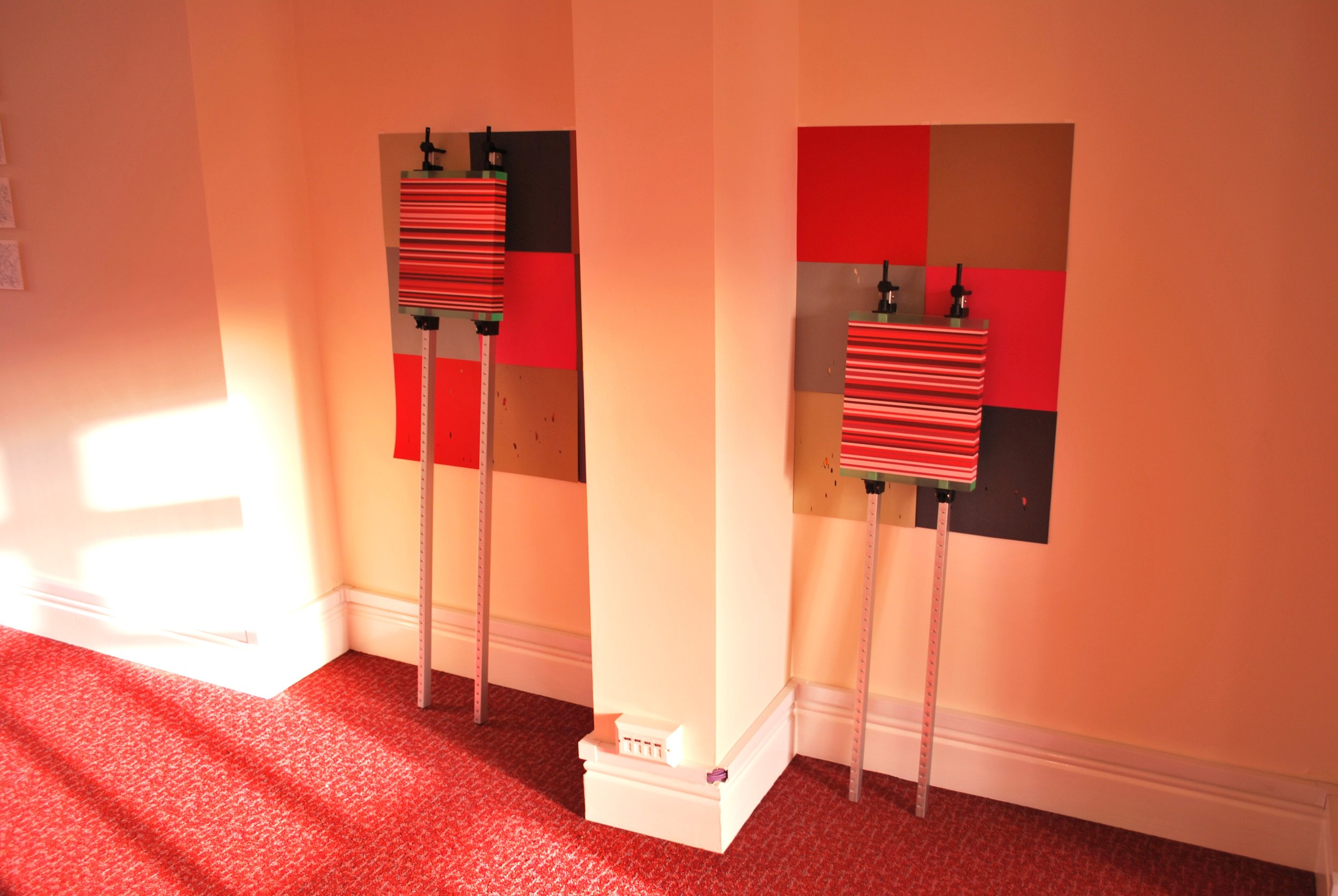

As we reach the top floor we find the work of Phill Hopkins who this time presents individual pieces from two on-going series’ of work; the ‘Occupy’ series and the ‘Fukushima’ series. The fragility of our existence and the space we occupy is made explicit in these works. A tiny matchstick house is placed at the centre of a dismantled speaker and with every crescendo of the Bruckner CD that is constantly playing, the house bounces around, no firm foundation and at the mercy of the elements. The drawings made at BasementArtsProject and presented on the wall at the Bridewell are here displayed on shelves in a cupboard. The drawings reference the barricades of the French revolution and draw connections with the ‘Occupy’ works. On this floor WalkerHill make their most definitive statements in terms of declaring the presence of their artworks. Each individual pane of the window contains its own painstakingly produced sequence of colours. Two slightly older clamp pieces lean against the wall allowing the colour sequences further into the room. Kelly Cumberland’s eight drawings sit on a wall opposite the work of Liverpool based artist Jacqueline F Kerr. The shapes within these framed collages echo Hopkins circular pieces to the left, and the tiny match books that make up a significant part of the largest map piece unwittingly seem to refer to Hopkins houses.

On the opening night 64 Wellington Street emits a warm and hospitable glow as the darkness of winter sets in and all of a sudden the title becomes something of a misnomer. But of course it never was about being Inhospitable, it was more a study of the reverse and how art fits in with other people’s ideas of hospitality and the social conventions surrounding the acceptance of art for its own sake.

On the subject of the difference between place and space in art terms Jean-Marc Bustamante has this to say

"One can certainly reproach art for evolving towards a complete autonomy that, while giving it great freedom, also cuts it off from the community. Inversely art could be considered a victim of society. Nevertheless, if one really wants to view recent developments in contemporary art close up, its relationship with architecture is very pertinent. This rapport comes from the artists’ desire to engage in a new dialogue with nature, with the city; their desire to take charge of a public space in a way that goes deeper than formal and decorative systems, which allows them to get back in touch with the world in a way that contrasts the in situ and site-specific concepts of the 1970’s"

From The Museum To The Town: Establishing Places Jean-Marc Bustamante; Dead Calm Exhibition Catalogue (2011)

When people talk about sites for exhibition they often refer to the ‘exhibition space’. The word space itself implies emptiness, nothing, a void, a non-place. Bustamante goes on to talk about how the word place indicates a ‘world of others’ and therefore a site for relationships with others; a relationship between artists, artworks and the rest of a society.

[1] Gablik, Suzy; ‘Has Modernism Failed’

Bruce Davies | November 2012